On January 6, 2024, Ramlal Nureti, a 25-year-old government teacher, was apprehended in Karekatta village, Chhattisgarh, on charges of allegedly posting Maoist banners and posters in September of the previous year. He was detained under the provisions of the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act of 2005. Meanwhile, villagers and schoolchildren from his village protested in front of the Sitagaon police station, demanding his release.

The legislation, introduced by the ruling party, Bharatiya Janata Party, had encountered criticism from certain members of the primary opposition party, the Indian National Congress. They asserted that the Bill was intentionally passed during a walkout by Congress legislators. The Bill was forwarded to the office of the President of India for assent by the Governor of Chhattisgarh, without being subjected to public discussion and debate.

The Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act of 2005 grants the central government extensive powers to curtail any “unlawful activities,” which it defines in section 2(e) of the Bill as any act or communication, verbally or in writing or by representation, by a person or organization:

- Posing a danger or fear concerning public order, peace, or tranquility;

- Posing an obstacle to the maintenance of public order, or having a tendency to pose such obstacle;

- Posing an obstacle to the administration of law or institutions established by law or the administration of their personnel;

- Intimidating any public servant of the state or central government by using criminal force or display of criminal force or otherwise;

- Involving the participation in, or advocacy of, acts of violence, terrorism, or vandalism, or other acts that instill fear or apprehension among the public, or involving the use, spread, or encouragement of firearms, explosives, or other devices destroying communication means through railways or roads.

Section 2(f) of the law stipulates that any organization engaged in any of the above (whether directly or indirectly) or whose aims are to further, aid, assist, or encourage, through any medium, device, or other way any unlawful activity would be deemed an “unlawful organization.” The act also empowers the District Magistrate (DM) to notify and take possession of places used for unlawful activities and other movable properties, including money, securities, and other assets.

Section 3(1) stipulates that the state government must only possess the opinion to declare any organization unlawful. The courts in Chhattisgarh have no right to inquire whether the DM or government had proof; their opinion and the convicted person’s tendency suffice.

The proposed Act has raised concerns from the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), an independent, international non-governmental organization working for the practical realisation of human rights throughout the Commonwealth. They believe this Act could be wielded as a tool to suppress free speech, stifle lawful dissent, and violate the fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution. According to a statement from CHRI, the current definition of “unlawful activities” jeopardizes the freedom to exercise fundamental liberties guaranteed by Article 19 of the Constitution. Specifically, it seems to restrict the ability to organize public protests, hold public gatherings, and utilize the media to critique government policies.

The Act significantly broadens the definition of unlawful activity, including punishing any act of verbal and written representations, and barring the media from carrying reports of any kind of ‘unlawful activities’ (Naxal/Maoist violence) in the state. The Act charges someone merely for having any ‘perceived intention’ and gives the state exorbitant power to describe what is “unlawful.” Moreover, it also grants the power to detain a member of an organization that the government deems unlawful.

A 2016 Amnesty International report, Blackout in Bastar, highlights the arrest of journalist Santosh Yadav under the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for allegedly supporting terrorist groups. The report describes ongoing attacks on journalists and human rights defenders, with arbitrary arrests, threats, and organized interference severely limiting their work. Local journalists investigating security force abuses have faced trumped-up charges and torture, while their lawyers have been threatened, creating a near-total information blackout in the region.

The CSPSA has drawn parallels with India’s sedition law, Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, which has been frequently invoked to silence government critics. Both laws allow the government to interpret dissent as a threat to the nation, punishing individuals for their opinions or associations rather than proven criminal actions. This raises concerns about the weaponization of legal tools to suppress any narrative contrary to the state’s, especially in regions like Chhattisgarh, where Maoist insurgencies have historically challenged the state’s authority.

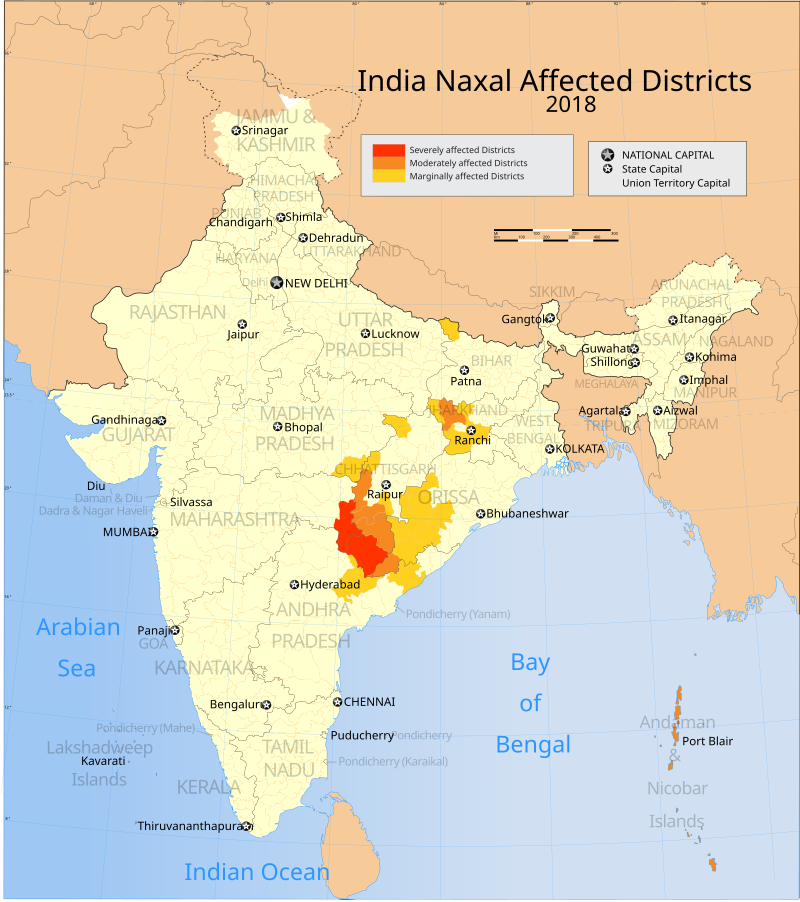

The focus on communism and Maoism in Chhattisgarh is rooted in the region’s long-standing history of Naxalite insurgency. For decades, Maoist groups have operated in rural areas, championing the rights of marginalized communities and fighting against what they perceive as exploitative state policies, particularly in the context of land rights and tribal welfare. The government has viewed this as an existential threat, leading to the militarization of conflict zones and the implementation of stringent laws like the CSPSA. However, the distinction between legitimate activism and violent insurgency has often been blurred. The term “urban Naxal” has emerged to label intellectuals, activists, and journalists who critique the state’s heavy-handed policies, conflating their ideological opposition with direct involvement in Maoist activities.

The recent move by the Maharashtra government to introduce a Public Safety Act, modeled after the CSPSA, reflects the growing tendency of Indian states to use such laws to combat not just terrorism, but any form of dissent. This widening scope has potential ramifications beyond the targeting of Maoists. It could set a precedent for criminalizing opposition movements, human rights defenders, and even academic discourse. By focusing on communism as the primary adversary, the state risks marginalizing voices that advocate for systemic change, often conflating legitimate criticism of governmental policies with subversion.